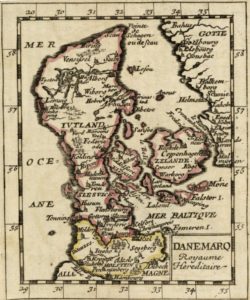

Between centuries 12nd and 16th, thousands of Scandinavians went on pilgrimage to worship Saint James the Apostle. Most of them were going to Rome and the Holy Land. There was a maritime route, the “West Path”, Vestvegr in Norwegian, which started in the Danish port of Ripe. There was another route on land, through the Jutland peninsula and across an old communication way known as the “Troupe Path”, Haervejen in Danish. This route received people from Skania, beyond the Øresund Narrows, which came through the islands of Zealand and Funen. There was another mixed route used by the Swedish, which started with the maritime stage from Stockholm to Lübeck (Germany). After that, the pilgrims would join the German paths in Hamburg towards France or the Netherlands, or they would embark on the west coast of Jutland to Galicia. The people who chose the maritime routes used to stop over on the coasts of the Netherlands, Great Britain and Brittany. If all went well, they would arrive to A Coruña or Ferrol’s ports, and continue through the English Path until Santiago de Compostela.

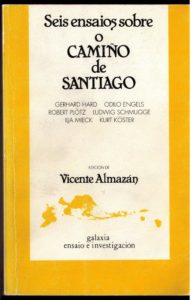

This centuries-long relationship between peoples so far apart and so different enriched the Jacobean phenomenon and left many marks on both, especially concerning Galicia and the worship of Saint James in Scandinavian territory. This is what we want to show in this exhibition: that Scandinavian Gallaecia which the medievalist Vicente Almazán (1924-2006) spoke about. This proposal is dedicated to him and to the researchers who dealt with the Jacobean phenomenon.

1. THE VIKINGS.

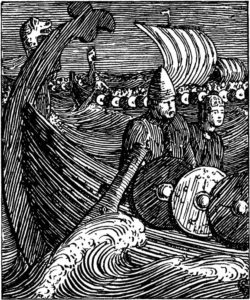

The Scandinavian coast’s weather is especially harsh during the winter. The prolonged bad weather and lack of sunlight hindered agriculture and trade. Due to this, since the 8th century, more and more riverside dwellers took up looting, robbing and extortion to add to their sustenance. They organized seasonal campaigns and made their way to neighbouring coasts attacking defenceless villages, taking with them animals, food and other valuable objects that they could sell.

Despite not being that different from other Scandinavian folk, Vikings managed to develop their own cultural risks regarding boat making, weaponry and even art pieces. Their lifestyle was so profitable that after hitting European coasts, they got into the Mediterranean Sea and established long-lasting bases. Historians talk about a “Viking Age” that lasted from 800 to 1050, characterized by constant invasions and colonisations that had influence on the political system of those kingdoms invaded.

1.1. THE SAGAS.

The Sagas are, therefore, collections of literary writings about the adventures of Nordic kings and commanders. Despite not being historical texts, they include real characters and discuss events that happened. Many times, they have historical veracity. One of these is the Saga of Ragnar Lodbrok and his sons, on which they based a famous TV show. Ragnar “shaggy breeches” Lodbrok was a Viking king, son of a Swedish commander who has been linked to the positioning of Paris in the 9th century.

The Sagas are, therefore, collections of literary writings about the adventures of Nordic kings and commanders. Despite not being historical texts, they include real characters and discuss events that happened. Many times, they have historical veracity. One of these is the Saga of Ragnar Lodbrok and his sons, on which they based a famous TV show. Ragnar “shaggy breeches” Lodbrok was a Viking king, son of a Swedish commander who has been linked to the positioning of Paris in the 9th century.

Heimskringla. It is a collection made up of 16 sagas about the Swedish and Norwegian kings, also known as “Old Norse Kings’ saga”. It was written by the skalda (the Court’s poet) Snorri Sturluson in 1225. The pages pictured are from “The Legendary Saga of St Olaf”, king of Norway from 1015 to 1028. They are the remainder of a 1260 manuscript lost in a fire in 1728, and they are kept in the National [and University] Library of Iceland.

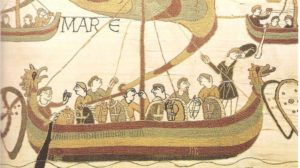

1.2. THE BOATS.

The skaldas (the Court’s poets) called it “sea horse”, “boar of the waves” or “float of the waves”. The drakkar, the most popular name, comes from the Icelandic word for dragon. It is a narrow, light and low draught rowing boat made out of wood. It is steered with a rudder to starboard (right-hand side of the boat) and has a mast for a sail. The average size would be of around 25 m (82 ft.) of length, 5 m (16.40 ft.) of beam and 1.5 m (5 ft.) of draft, with 32 oars and room for 75 people. Of course, these boats varied in size depending on their use; e.g., for transportation, fishing or war. Romans already knew about them in the 1st century AD, since the historian Cornelius Tacitus called them “swedes”. They were not built using chains, instead the wood planks were put on top of each other and later. the joints were covered with tar-soaked moss. For maximum resistance, they tried to achieve this with one piece, so they looked for trees that allowed that.

How did they orientate? How did they sail? It is hard to explain how Viking ships managed to sail successfully across the Atlantic Ocean before 1300, when compasses started being used in vessels. A possible explanation is that they used Iceland spar, the “sun stone”, a transparent calcite that can only be found in that island. Since it has refraction, it would help position the Sun even in cloudy skies. Some go further and say that the round wooden fragments that have been found in Viking settlings, the “Unnatoq disks”, make up, along with the “sun stone”, a device that locates the sun through the shadow lines.

How did they orientate? How did they sail? It is hard to explain how Viking ships managed to sail successfully across the Atlantic Ocean before 1300, when compasses started being used in vessels. A possible explanation is that they used Iceland spar, the “sun stone”, a transparent calcite that can only be found in that island. Since it has refraction, it would help position the Sun even in cloudy skies. Some go further and say that the round wooden fragments that have been found in Viking settlings, the “Unnatoq disks”, make up, along with the “sun stone”, a device that locates the sun through the shadow lines.

The embroidery board is a simple system of navigation through estimation that allows you to register the speed and route of the ship for a sentry. There is no need to write anything down, it is merely a memory assistant. It is so simple that it can be used by any sailor, whether they are literate or not.

Pilgrims did not always follow geographical criteria when choosing their paths. Instead, they tried to pass by the tombs of heroes and the places with relics or cult images. The oldest record of the Danish Kingdom is dated back to 985, when the Jelling runestone was engraved: “Harald… King that conquered Denmark and Norway and converted Norwegians to Christianism”. He died in 986, approximately.

According to Nicholas Bergsson, Benedictine Abbot at the Pverá monastery in the middle of the 12th century, Icelandic people disembarked at the Aalborg port in Denmark and walked to Vyborg for two days. It took them a week to go from there to Hedeby, and one extra day to get to the Eider River, near the current Kiel, where they joined the German paths.

We know through the handwritten notes of the bishop Adam of Bremen (1050-1085) that there was a sea route to Compostela in the middle of the 11th century from the old Ribe port, in the Western Jutland coast. It connected with the Zwijn estuary in the Netherlands; Prawle Point, in the South of England; Saint-Mathieu, near Brest in Britain; and from here to A Coruña.

4.1. HAERVEJEN, "THE OX ROAD".

Hærvejen or “The Ox Road” is an ancestral way that conjoins the North of the Jutland peninsula with German land. It ended at the old border between Denmark and Germany, the so-called Dannevirke, located between Flesburg and Kiel, current Germany. It has been known since Viking times (800-1000) as the way of communication with the rest of Europe. Vicente Almazán thinks of it as “St James Way” due to the amount of pilgrims from Denmark, Iceland and Norway that arrived at Compostela through it.

You would enter the city of Vyborg through the St James’s Gate, which no longer exists but can be located because it is marked on the ground. This gate led to St James’s Street (Sct. Ibsgade), which still exists, and halfway through it to the right the St James Church, now gone, rose.

Not far from the Ox Road, near Søvind (12 km/7.5 miles before Horsens) there is a “healing” fountain called “St James’s Fountain”. At the South of the path, there is a “pilgrim hill” (Pilgrimshøj). There are also churches in Aarhus (1306), Allerup (1407) and Gladsaxe (1322).

4.2. THE DANISH WAY. FUNEN, ZEALAND, SCANIA.

Pilgrims that came from the East, from the land that framed the Danish riverside by the Øresund strait and the land across in Scania,went through the islands of Funen and Zealand before joining the Hærvejen in Jelling through Kolding. That is why there are churches and chapels dedicated to St James in Roskilde, the old Danish capital, and Bornholm Island, among other stops along the way.

Some Danish pilgrims. The first Danish pilgrim that we know of is Axel Absalon (ca. 1128-1201), born in Zealand, he visited Compostela in 1181. He was advisor of King Valdemar I of Denmark and Canute V, bishop of Roskilde from 1158 and archbishop of Lund in 1177. There are records from 1190 of a man called Winido and his wife, parents of a boy sentenced for murdering another boy by the Eider River. This river was at the then border between Denmark and Germany.

Some Iceland pilgrims. In 1354 the Icelanders Olaf Bjarnarson and Gudmund Snorason travelled by sea to Compostela, but died in a shipwreck. In 1402 – The Icelander Björn Einarson (1350-1415) travelled to Jerusalem by boat and, on his way back, he decided to go to Compostela from Venetia as his wife went back home to Iceland. He wrote a book about his journey, but it got lost.

Some Iceland pilgrims. In 1354 the Icelanders Olaf Bjarnarson and Gudmund Snorason travelled by sea to Compostela, but died in a shipwreck. In 1402 – The Icelander Björn Einarson (1350-1415) travelled to Jerusalem by boat and, on his way back, he decided to go to Compostela from Venetia as his wife went back home to Iceland. He wrote a book about his journey, but it got lost.

Some Norwegian pilgrims. The first Norwegian pilgrim to Compostela was the king Sigurd Jorsalafar “the Crusader” (1090-1130), who arrived by sea in 1108 with his Viking fleet on his way to the Holy Land. After Compostela, he went south and helped the Count of Portugal conquest land from the Muslims. In 1152, Rögnvald III (St Ronald), Earl of Orkney, arrived following King Sigurd’s route. Fleets of Norse, Irish, Rhenish and Frisian men also arrived during the Third and Fourth Crusades on their way to Jerusalem.

St Andrew of Slagelse, Danish pilgrim.

St Andrew of Slagelse, Danish pilgrim.

He was a priest for St Peter in Slagelse on 1205. According to legend, he went to Holy Land with a group of pilgrims. On the day they were supposed to go back home, as his companions embarked, he stayed behind saying mass. A rider on a white horse picked him up on Easter in the year 1200 and brought him back to Slagelse flying. The rider left St Andrew at the “hill of rest”, at the entrance of the town, where lays a cross to remember the miracle since 1677. The day after, Andrew left for Compostela and stopped at St Olaf’s tomb in Trondheim (Norway) on his way back. He followed the same route as his companions and made it back from the Holy Places before they did. In Slagelse, there is also a well dedicated to him, Helling Anders Kilde.

According to Vicente Almazán, the last Danish pilgrim was the Franciscan Jacobus Dacianus during the first years of the Lutheran Reformation, which ended pilgrimage. Jacobus lived in Spain from 1539 to 1542; he was born in Copenhagen in 1484 and died in Tarecuato (Michoacan, Mexico) in 1566 or 1567. He was the third son of King John (1481-1513) and Queen Christina of Saxony (dec. 1521), and therefore brother to Christian II (1513-1523).

He was the last of the Provincial Franciscans in Denmark, under the name Jacobus Gottorpius in 1537. The Danish writer Henrik Stangerup wrote about his life (Broder Jacob, Copenhagen, 1991 / Frey Jacob, Tusquets, 1993) and talked about his stay in Compostela in the pages 103 and 125 (Almazán, p. 48, Dinamarca Jacobea).

Almazán claims he could not find information on Danish pilgrimages after 1526. He also highlights that the St James Brotherhood from Odense received money from Queen Christina of Denmark, as well as the existence of a document dated September 17th 1515 that grants papal authority to Oluf Nielsen, vicar at the St Nicholas Church in Copenhagen to grant all Compostela pilgrims an indulgence.